Olympic Villages have accompanied Olympic Games since the Olympics in Los Angeles, 1932. The Village designed for the Helsinki Games in 1952 was the first intended to be converted into housing. Now, following Helsinki’s example, Olympic Villages are often converted into residential units, with rare anomalies such as Lake Placid 1980, which now stands as a federal prison. However, the success of each Village in their subsequent uses still vary immensely, depending on many interconnected factors such as sustainability and economic growth.

The Tokyo 2020 Olympics Village is set to be converted into a 13.9 hectare residential sub-division, ‘Harumi Flag’, by ten large developers, including prominent companies like Nomura Real Estate and Mitusi Fudosan Residential. Plans anticipate that the development, located in the centre of Tokyo on man-made island Harumi, would consist of over 23 residential buildings and a commercial facility, as well as other leisure and social services, such as parks and childcare facilities.

Source: https://news.panasonic.com/global/stories/2019/71599.html

Whether or not these flats remain vacant in 2024, which is when the flats are set to be completed, cannot be determined for sure at this point. Despite this, after taking a look at the Sydney (2000), Athens (2004), Beijing (2008), London (2012) and Rio de Janeiro (2016) Olympic Villages it can be seen that there are a few common criteria that distinguish the successes from the failures. These include the economic state of the host country, whether private or public developers are in charge, how much emphasis is placed on sustainability and the amount of careful planning involved. The location of said Villages can also be taken into account, however this point may be secondary to the rest as it can be argued that with good planning and a decent transport system, such as will be seen in the case of London, distance from the city centre is not as significant a factor. When the pattern that successful Olympic Villages have followed is identified and compared with the journey of the Tokyo Olympic Village so far according to the criteria listed above, the future of the Village seems optimistic.

Past Olympic Villages

Sydney (2000)

The Sydney Olympic Village was a remarkable success. Built in Newington (inner-west Sydney) and developed by a public-private partnership, it was a major stepping stone in terms of sustainability, and reportedly ‘changed urban planning and design in Australia forever’, in particular the development of greenfield sites. Unlike previous Villages, it was designed as permanent housing, and ‘used the principles of permanent dwellings that had game overlays to deliver the beds required for athletes’. For example, demountables that could be easily removed were placed in backyards and removed after the Games.

Source: https://www.projectanalysis.com.au/olympic-athletes-village-demountable/2923

Rooms were also big enough for divisions to be placed inside. This meant that their target market – Sydney’s middle class , or even the general public, would be more willing to put their money forward and purchase housing as these residences were built more like a permanent home to live in rather than for a two-week temporary stay.

Source: https://placesjournal.org/assets/legacy/media/slideshows/gade-olympic-villages-18.jpg

Furthermore, the emphasis placed on sustainability during its construction, with the area being the largest solar-powered suburb in the world, boosted the its status and bolstered its image, adding onto the pre-existing attraction of it being a former athlete’s village. Another factor that contributed to its success was the real estate boom and overall favourable growth in the economy at the time, which eliminated the risk of being unable to finance construction due to sudden large falls in consumer confidence and subsequently consumption. It meant that consumers were more eager to purchase new housing and so demand was able to meet supply more easily.

Athens (2004)

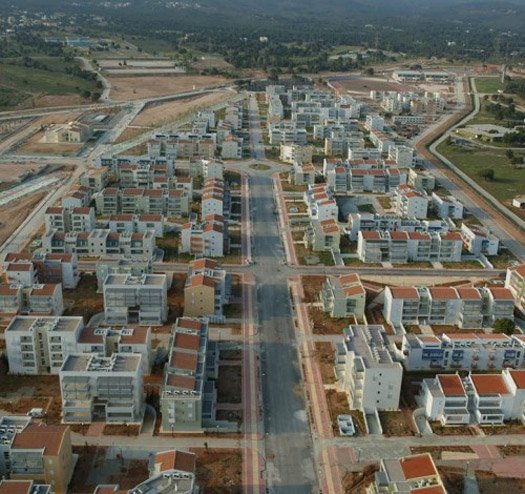

The Athens Olympic Village (2004) was to be turned into the ‘biggest social housing development in Greek history’ and was constructed on brownfield (‘degraded, polluted, minimally inhabited wasteland on the city’s far northern outskirts) land. It was a huge failure, with many flats now vacant and the infrastructure dilapidated. Its use as public housing, distributed to citizens through a lottery, diverged from the Olympic Village in Sydney, which was built to be sold as housing for those in the middle-class. Another aspect that differed from the successful Sydney Olympic Village was that it was built using ‘old, environmentally unfriendly technology’. Furthermore, even as the athletes were moving into the village, there was already criticism surrounding the living conditions, with some citing bad security and the housing being unfinished.

source:https://placesjournal.org/assets/legacy/media/slideshows/gade-olympic-villages-19.jpg

One core reason that it failed was that the costs for the event were underestimated due to a lack of careful planning and excessive extravagance. Greece simply could not afford the Olympics. The municipalities responsible for developing the area did not have the funds to sustain redevelopment and so the planned infrastructure and schools were never constructed, which inevitably withdrew from the value of the area. Another important factor to consider is the prolonged economic recession that Greece fell into later on, which the Games undoubtedly contributed towards. The following recession and debt crisis even more so meant that there were not enough funds to pay for the development. The lack of private sector involvement should also be taken into account – with Jay Scherer citing the Village as a ‘sobering portrait of the level of debt that can be accrued by the state in the absence of private investment in these developments’. There was also a lack of deliberation in terms of ‘environmental strategy and forward thinking’, or ‘economic feasibility studies or even a basic business plan’ as planners rushed to finish venues, leading to the soaring costs of the Games (cost nearly $11bn and double the initial budget), leaving diminishing funds behind to actually redevelop and maintain these venues.

Beijing (2008)

Less is known about the reality of the Beijing Olympic Village (2008) now, but it was developed into housing for upper-class Beijing residents and has gravitated towards Newington, rather than Athens’ example. Environmentally-friendly amenities were also included, with the Village being equipped with geothermal energy and solar panels and a micro-energy building, and reportedly, the city ‘tied its Olympic agenda to long-term land use development goals’. This increased the appeal of the units, which would have led to a rise in demand for them. According to China Daily, even people from outside Beijing expressed interest in the condos after the Olympics. Ge Huai’en, the Village’s marketing director, also stated that ‘about 70% of the apartments in the Olympic Village in northern Beijing had been sold before the Olympics’. The price of these flats practically doubled in a year and a half following their market release and surrounding real estate values rose.

Source: https://medium.com/@toby.lr/beijings-2008-olympic-developments-8-years-later-3f45a95d1171

London (2012)

The London Olympic Village, now converted into a neighbourhood north of Stratford town centre known as East Village, was developed on brownfield land, following the example of the 1992 Barcelona Games. Forbes has labelled East Village (and Olympic Park) as a ‘rip-roaring success’, and Ben O’Rourke claims that the London Olympics’ real-estate legacy is largely responsible for ‘London moving east’. Of the 2,818 new residences created, 1,379 were labelled as affordable homes and sold to Triathlon Homes. The remaining private homes, plots for a potentially 2,000 more residences and long-term management of East Village are managed by Get Living London and owned by Delancey/Qatari Diar. Now, East Village is labelled ‘London’s Hippest Postcode’, with its architecture looking to ‘emulate the much-loved planning of Maida Vale and other parts of Victorian west London’ and is a ‘rare example’ of a housing devlopment that ‘shows more thought and quality than most things comparable built in Britain in recent decades’.

Source: https://inhabitgroup.com/project/east-village-london-e20/

East Village offers a variety of housing types, from apartments to townhouses and the neighbourhood also has facilities such as a school and health centre. Its transport links also serve as a major drawing point, for example, King’s Cross is fifteen minutes away, so despite its location, people are not overly deterred by that. The East Village’s success could be attributed to the dire need for affordable housing in London, especially following the Global Financial Crisis 2007-08. Overly high housing costs have long been an issue for Londoners, and naturally the housing in the East Village, part of which was marketed to be affordable, would have been in high demand and appealing to the public. The East Village was also designed with the environment in mind, with integrated transport, green open spaces (green roofs, wetland area, fruit trees etc.) and flats that adhere to a ‘high standard of energy-efficiency and insulation’. Long-term development was taken into account as well, with plans to have 24,000 new homes built in the area by 2031.

Rio De Janeiro (2016)

The Rio de Janeiro Olympic Village (2016) is, as Forbes describes it, a ‘ghost town’. It was built in the West Zone of Rio, in an upper-class neighbourhood. In a way, it was similar to Newington in that it was going to be developed as luxury housing, however the developer billionaire Carlos Carvalho seemed to lack an awareness of the true amount of demand for his luxury condos. He envisioned a ‘city of the elite, of good taste’ and that ‘for this reason, it needed to be noble housing, not housing for the poor’, with prices as high as $700,000. He may have had overly-ambitious prospects for the Village, which helped cause its current vacant state.

source:https://architectureofthegames.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Rio-2016-Olympic-Village-Apartments-on-sale-in-June.jpg

The key difference here between Rio and success stories like Newington is the overall financial state of the host countries – Sydney’s economy was arguably more stable, and there was a larger demand for middle-class or luxury housing than in Rio, where there is an ever-widening gulf between the rich and poor. Had there been increased community consultation and a greater awareness of what Rio actually needed, instead of purely focusing on financial motivation, as Carvalho seemed to have done, the project may have been more successful. Another factor, as Isabel Swan states, ‘I feel the Olympic Games in Brazil were not so successful because the legacy was not the number one concern’. The economic downturn and large fiscal deficit in Brazil did not help matters, and only 240 of the 3,600 units had been sold two weeks before the opening ceremony of the Games. Even now, apparently 93% of the condos are vacant. Furthermore, the Village during the Games did not have particularly favourable reviews either, with Kitty Chiller, the Australian Olympics boss, claiming that the units were ‘unliveable’. There are notable similarities between Athens and Rio – poor economic state, poor governance and poor time management, with both countries’ venues being built in a rush.

Tokyo’s Future

The successful Olympic Villages have several factors in common. They tend to be built as residences to be sold to the middle to higher classes, and the environment is often a priority. The economy, in particular the real estate market of the host country, also tends to be stable. Furthermore, if the host country is developed, this improves its chances on developing the Village aptly as there is a larger probability that they would have the funds to sustain this, especially since the opportunity cost of them hosting the Games in general is lower as they would likely already have most of the infrastructure required.

The Tokyo Village has already received favourable reviews from athletes on prominent news and social media platforms, enhancing its image for prospective buyers even more. Private developers would be responsible for ‘specific aspects’ of development due to their ‘capabilities and know-how’ to turn the former Village into a ‘new and convenient community where a diverse range of people live and interact with ease and comfort’ under a public-private partnership. Looking back at previous Olympic Villages starting from Athens, the successful cases tend to have some amount of private involvement.

Housing Plans: https://www.2020games.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/modelplan_e.pdf

Source: https://news.panasonic.com/global/stories/2019/71599.html

Furthermore, it appears that the development has been carefully planned out with long-term environmental goals in mind, similar to the successful cases of Olympic Village development – as stated on the website, they hope to ‘prepare an environment that will be passed down to the next generation’. Although not permanent, the viral cardboard beds that the athletes slept on is already an indicator that sustainability is a prominent element of this year’s Village. Environmental stability is an attractive element for prospective buyers and could increase the property’s value. Moreover, developers plan to install a hydrogen energy system and to use AI to forecast power demand, conserving energy. A ‘real forest’ is also in the works, and Harumi Flag hopes to create an ecosystem, complete with a hybrid irrigation waterscape and animals. The website continues to outline the effort being put into the design and redevelopment of the area, for example noting that the skyline would create a ‘rhythmic silhouette’ (translated), and outlining careful details such as light controls for ambience, non-slip pavements and more. These design details hint at the in-depth and long-term planning being put into Harumi Flag, which is a good sign for the future.

During Phase 1 of sales to the public in May 2019, where 600 flats were released, there were already 7 applications for every flat released. In July 2019, more than 2,000 applications were made for the further 900 flats put on sale as well. Although sales were halted due to the pandemic, they are expected to resume following the Olympics this autumn. Whether or not demand would remain as significant remains to be seen, however, when looking at the state of the real estate market in Tokyo, prospects seem to be positive. Owing to Japan’s extremely low borrowing cost, there is ‘persistently high occupancy, stable and resilient rental income and attractive pricing’, says South China Morning Post, even calling Japan’s real-estate market ‘Asia’s star performer’.

Of course, there are concerns. The lack of communication from developers to buyers about the delays due to the pandemic have led to buyers’ complaints making headlines, which may deter other prospective buyers. Market trends cannot be determined for sure either. Only time will tell, but for now, the future of the Tokyo Olympic Village certainly seems a lot more favourable than that of Athens or Rio.

Reference:

- https://www.archdaily.com/964471/olympic-urbanism-the-afterlife-of-olympic-parks-and-stadiums

- https://resources.realestate.co.jp/news/demand-soars-for-tokyo-2020-olympic-village-apartments-to-be-repurposed-as-private-condominiums/

- https://www.flat-chat.com.au/olympic-village/

- https://www.flat-chat.com.au/olympic-village/

- https://www.rfi.fr/en/economy/20150705-struggling-survive-greeces-olympic-villagers-face-referendum-choice

- https://www.realestate.com.au/news/olympic-villages-past-and-present/

- https://www.rfi.fr/en/economy/20150705-struggling-survive-greeces-olympic-villagers-face-referendum-choice

- https://www.foxsports.com.au/olympics/worst-athletes-villages-in-games-history-amid-concerns-over-rio-2016-accommodation/news-story/335ff29947f742d1765354f62c33f11a

- https://www.realestate.com.au/news/olympic-villages-past-and-present/

- www.jstor.org/stable/42857457

- https://medium.com/@toby.lr/beijings-2008-olympic-developments-8-years-later-3f45a95d1171

- https://www.realestate.com.au/news/olympic-villages-past-and-present/

- http://www.asiabusinesscouncil.org/docs/BEE/GBCS/GBCS_OlympicVillage.pdf

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/161451058.pdf

- https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/olympics/2008-09/12/content_7023975.htm

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/161451058.pdf

- https://www.archdaily.com/964471/olympic-urbanism-the-afterlife-of-olympic-parks-and-stadiums

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/bisnow/2017/07/25/five-years-on-londons-olympic-real-estate-legacy-is-a-clear-winner/?sh=70049cc81364

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/jan/08/athletes-village-olympics-2012-architecture

- https://www.internetgeography.net/topics/sustainable-urban-living-east-village/

- https://inhabitgroup.com/project/east-village-london-e20/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/keithflamer/2017/02/28/the-olympic-shames-rio-and-athens-sports-venues-abandoned/?sh=12cbe762ca0c

- http://www.phantom-urbanism.com/rio-de-janeiro-olympic-village.html

- https://www.bbc.com/sport/olympics/39323546

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt1vjqnp9.13?seq=16#metadata_info_tab_contents

- https://www.realestate.com.au/news/olympic-villages-past-and-present/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt1vjqnp9.13?seq=16#metadata_info_tab_contents

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt1vjqnp9.13?seq=26#metadata_info_tab_contents

- https://www.2020games.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/eng/taikaijyunbi/torikumi/facility/sensyu/modelplan/index.html

- https://www.31sumai.com/mfr/X1604/#!/article/19

- https://resources.realestate.co.jp/news/demand-soars-for-tokyo-2020-olympic-village-apartments-to-be-repurposed-as-private-condominiums/

- https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2020/03/c86c71dab2d5-athletes-village-condo-buyers-fret-after-tokyo-olympics-delay.html?phrase=14%&words=

- https://japanpropertycentral.com/tag/harumi-flag/